Historic Landscape Characterisation

Blaenavon

Blaenavon is located at the head of the Afon Llwyd valley in one of the more exposed areas of the Gwent uplands. The lowest part of the town, where the river enters the narrow valley floor, is at 300m above OD. The valley sides rise fairly steeply to the surrounding moorland ridges of Cefn Coch, Coity Mountain and the Blorenge which reach almost 600m above OD. The Pwll Du area, to the north of the town, occupies the plateau forming the watershed between the Afon Llwyd valley and the Clydach gorge to the north.

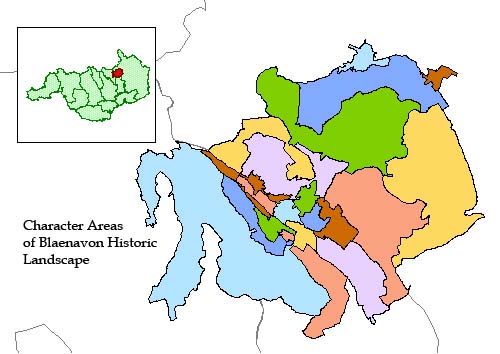

Use the map to select your area of interest or go directly to character area summaries.

The whole area is covered by early, coal opencasts and it survives as probably the only sizeable, abandoned, multiple period, opencast mineral working in South Wales. It remains a palimpsest of early mineral working and processing, crisscrossed by shallow trench mines, tramway inclines and tips. These elements, with the town of Blaenavon, Coity Mountain, the Blorenge and Pwll Du, and a preserved mining scenery directly related to the mining processes, form the essence of the unique historic character of the landscape of Blaenavon. Until the late medieval period, the area was primarily used for sheep grazing and it was not until the late 16th and early 17th centuries that any form of settlement associated with iron exploitation appears, although the area was richly endowed with all the requirements for ironmaking, with , woodland, limestone, coal and good quality ironstone available in abundance. Between the 1670s and 1790s iron ore was being exploited on a small scale on lands immediately to the north of the present town, however the large-scale, commercial development of the local mineral wealth only began with the establishment of the Blaenavon Ironworks in 1789.

The succeeding industrial development of Blaenavon can be traced through the changes that have occurred to the surrounding landscape, which dramatically still bear witness to the activities of the coal, iron and steel industries, with the remains of quarry workings, mine shafts, open casting patches, extensive spoil heaps, tramroads and railways still apparent. Indeed, the vast desolate spoilheaps of the Blorenge forms a distinct landscape in its own right, dramatic and grim, and provides a unique reminder of the Welsh industrial past and of man's technological development, which saw the wholesale alteration of the South Wales landscape at large.

The town of Blaenavon is one of the best surviving examples in South Wales of a valley head industrial community, retaining many characteristic features from the 19th century such as terraced housing, shops, churches, chapels, schools and the Workman's Hall and Institute.The town retains the vital link between the residential, commercial and religious elements and the associated industrial sites and man-made landscape. The original core or the town, dating to the 1790s and based on North Street, is still evident in some of the surviving groups of buildings. These include St Peter's Church (1804), the only 18th century styled church which has cast iron tomb covers, window frames and font.The adjacent school buildings, in matching mock-Gothic style, were constructed and endowed in 1816 in memory of Samuel Hopkins, one of the proprietors of the local ironworks, specifically for the educational welfare of his workers. Although many of the original workers' houses have been demolished, many still remain, notably those opposite to the Blaenavon Ironworks. In addition, and in contrast, the residences of some of the early proprietors of the Blaenavon Company survive, such as at Park House and Ty Mawr, since converted into a hospital.

The later development of Blaenavon during the period 1820 to 1870 is reflected in the area bounded by King Street in the north and Hill Street to the east. The area is typified by simple four-roomed houses, some also provided with cellars. More elaborate dwellings, such as Vipond House and Ton Mawr (The Arundel Club) exist alongside. Other notable community buildings include the Horeb Chapel (1862 ),with its classic Ionic style, the Police Station (1867), the Workman's Hall and Institute (1894), which is an interesting example of an early social and recreational centre; and, of course, numerous public houses. Broad Street and the adjoining terraced rows illustrate the traditional urban landscape of a South Wales valley town, a type of institutional development that has largely disappeared from other regions.

Blaenavon contains two nationally important sites preserved as examples of the area's rich industrial legacy: the Blaenavon Ironworks and the Big Pit Mining Museum, both important historical and technological components in the industrial and social landscape of Blaenavon.

The Ironworks, a Guardianship Site, are remarkably well preserved. The first Blaenavon Ironworks, constructed in 1789 as an early coke-fired works, utilised the natural terrain. A bank of furnaces were constructed into the hillside which enabled them to be charged from the upper level, whilst, after blasting, allowing the molten metal to run, off at the base into the casting houses, where it was moulded into pigs. The structures of the furnaces and the two casting houses survive well.

A water balance lift is a very dominant structure. Built some time after 1839, it is an impressive hydraulic lift which was used to carry tram loads of iron from one level to another so that they could be transported by tramroad to the nearby Garn Ddyrys Forge, and also to the Brecon and Abergavenny Canal which forms an equally significant element in this large interconnecting industrial landscape. In addition, there is an important surviving group of workers cottages at Stack Square.

The former Big Pit Colliery was sited on the easternmost side of the South Wales coalfield. In 1980, it closed as a working mine and is now run by a charitable trust providing visitor access to descend 90m underground. The colliery was sunk to its present level in 1880, though its underground workings incorporate much earlier shafts and tunnels, one example being Forge Level, which was driven in 1812 to supply coal specifically for the Blaenavon Ironworks. Below ground, engine houses and stables still remain. On the surface, the steel headgear dated to 1921 and the associated ranges of buildings demonstrate the extent of the former colliery. These buildings include the pithead baths, blacksmiths' shop, lamproom, winding engine house and tram circuit. This site remains as a well-interpreted, yet rare, example of a colliery which contributed to the establishment of very distinct Welsh communities set in the landscapes they created.

Associated with the industrial exploitation of the area are the remains of the transport network, required to convey the raw materials to the ironworks and export the finished product. The area contains a variety of transport features, ranging from small tramroads through to major monuments such as the tunnel and the dyne steel inclined plane at Pwll Du. The tunnel was opened in 1815 to transport limestone to the ironworks from the quarries to the north. It also took pig iron from the ironworks to the forge at Garnddyrys, but it was eventually superseded by the dyne steel inclined plane in about 1850.

The landscape of Blaenavon, although subject to reclamation schemes such as at Kays and Kears, remains one of the best preserved, relict industrial landscapes in Wales, containing a vast concentration and diversity of archaeological features. It also serves as one of the most powerful reminders of the Welsh Industrial Revolution, and man's exploitation of, and dramatic impact on, the landscape.